Leaving Certificate Teacher Resources

The Georgian Beginnings of Henrietta Street

Syllabus links:

- The end of the Irish kingdom and the establishment of the Union, 1770-1815

- Ireland and the Union, 1815-1870

Henrietta Street is the earliest Georgian Street in Dublin. Construction on the street started in the mid 18th century, on land owned by Luke Gardiner. Henrietta Street quickly became Dublin’s most exclusive address, attracting the leading figures from Ireland’s governing elite. In its first thirty years Henrietta Street was home to no less than six titled residents, two army generals, three archbishops, two speakers of the House of Commons and the Lord Chancellor of Ireland. These high-class town houses were social settings and political arenas, the scenes of parties, strategising and intrigue. Almost all of the Georgian residents of Henrietta Street were involved in politics or law, from MPs and Lords to powerful churchmen. They included Lord John Maxwell (Baron Farnham); Owen Wynne (MP for Sligo); the Earl of Thomond; George Stone (Bishop of Ferns); Nathaniel Clements MP; William Stewart (Earl of Blessington); Sir Robert King (Baron Kingsborough); and Nicholas Hume-Loftus (Earl of Ely).

After the Act of Union in 1801, many fashionable Dublin streets fell out of use as the aristocracy and socialites moved away. This period saw the rise of the professional middle classes such as doctors and lawyers, and the proximity of the King’s Inns at the top of Henrietta Street led to the area becoming a legal enclave, where solicitors lived, trained, and worked. From 1800 until the 1840s 14 Henrietta Street was the home and office of solicitors.

The Great Famine of the mid 19th century led to the establishment of the Encumbered Estates, which was set up to handle the large number of country estates that had become insolvent. The Encumbered Estates Court was established at 14 Henrietta Street, and the coach house at the back of the building was turned into a courtroom. From 1849 the purpose of 14 Henrietta Street was to manage the sale and settle the debts of these huge estates.

From 1862 until 1876, the fortunes of the building changed yet again when it became a barracks for the Dublin militia and was lived in by soldiers and their families. It was around this time that other buildings on the street started to be made into tenements. The soldiers did not make good neighbours for the members of the legal profession who still worked on the street, who made formal complaints to the government about the noise of their drilling, and in 1876 the militia left.

Humans of Henrietta Street

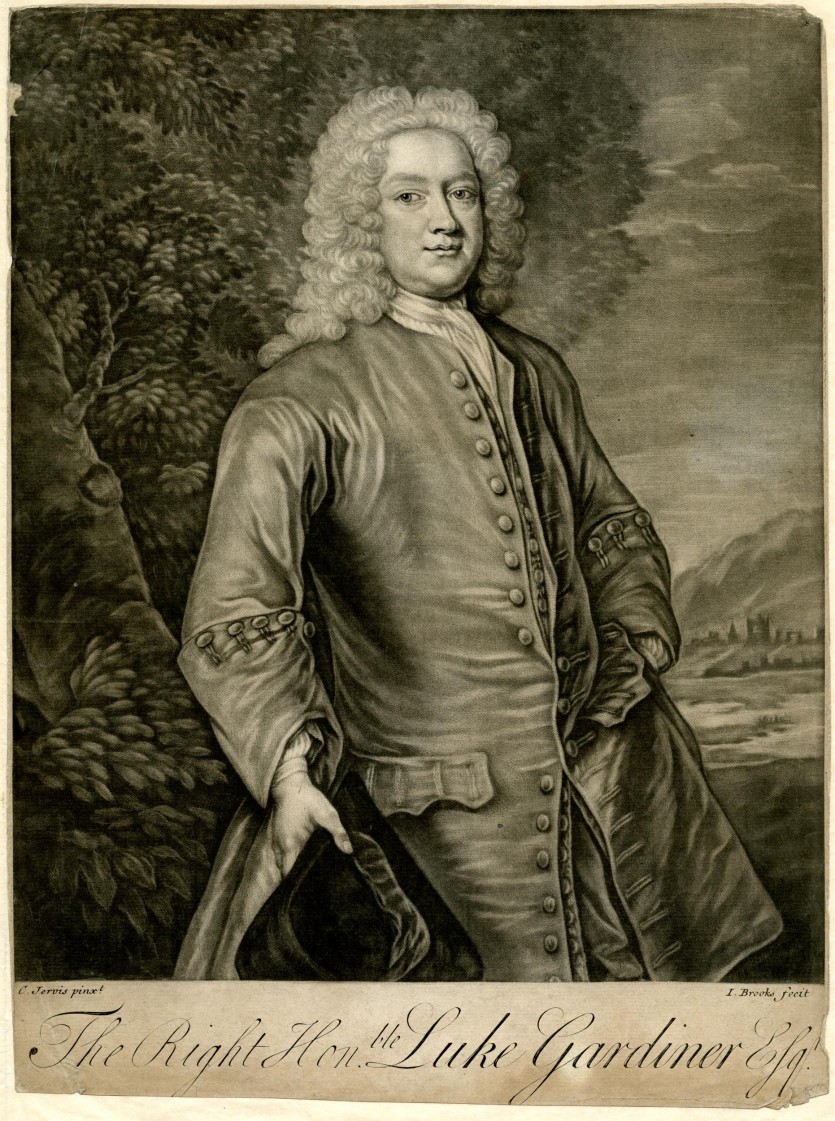

Luke Gardiner (a.1690 - 1755)

Henrietta Street was developed by Luke Gardiner. We know very little about Gardiner’s early life, origins or parentage, but he is believed to be a native of Dublin City. He became one of the most successful and wealthiest men in Ireland. He was an MP, a banker and as a property developer he shaped the face of the northside of Dublin. He developed Gardiner St, Mountjoy Square, Marlborough Street, and for Ireland’s elite and powerful he created Henrietta Street.

The street was named for Henrietta, Duchess of Grafton whose husband was Lord Lieutenant of Ireland at the time.

Viscount General Richard Molesworth (1680 - 1758)

Lived in 14 Henrietta Street: 1751 - 1758

The first family to occupy 14 Henrietta Street was the Molesworths: Viscount General Richard Molesworth of Swords and his second wife Mary. Richard Molesworth had a distinguished military career and led his regiments at the Battles of Blenheim (1704) and Ramillies (1706) during the War of the Spanish Succession. He was appointed Commander-in-Chief of the Royal Irish Army in 1751.

Molesworth’s daughter by his first wife was Mary, Lady Belvedere. Her husband held her under house arrest in Gaulstown, Co. Westmeath for nearly thirty years, as he believed she had been unfaithful to him. Mary denied the accusations, but her family disowned her over the scandal. Once, she escaped and fled to 14 Henrietta Street for her father’s help, but he turned her away.

Lady Mary Molesworth (1728 - 1763)

Lived in 14 Henrietta Street: 1751 - 1758

Born Mary Jenney Usher, Lady Mary Molesworth was only fifteen years old when she married Richard Molesworth in 1743, who was then sixty-three. She was described by writer Horace Walpole as a “very great beauty,” whose “amiable character’ and virtue were ‘beyond all suspicion, untainted and irreproachable.”

Lady Mary had eight children, and died in 1763 in a house fire in London, along with her brother and two daughters Mary and Melosina. The fire was a result of arson: a servant trying to cover up a theft.

John Bowes (1691 - 1767)

Lived in 14 Henrietta Street 1758 - 1767

John Bowes was an Anglo-Irish politician and judge. He was noted for his legal ability and his hostility to Catholics.

He once ruled during a land dispute that: "The law does not suppose any such person to exist as an Irish Roman Catholic, nor could such a person draw breath without the Crown's permission." Such extreme views made him very unpopular.

He lived at 14 Henrietta Street until his death. There is a monument to him in Christchurch Cathedral, Dublin.

Mary Wollstonecraft (1759 - 1797)

Lived in 15 Henrietta Street 1786 - 1787

Mary Wollstonecraft moved next door to 15 Henrietta Street in 1786 to work as a governess for the three eldest daughters of the Kingsborough family. She did not get along with Lady Kingsborough and was dismissed the following year. Five years later she wrote the pioneering feminist book A Vindication of the Rights of Woman.

Wollstonecraft gives us a look at a Dublin where women were expected to abide by what she regarded as oppressive social rules: “Dublin has not the advantages which result from residing in London; everyone’s conduct is canvassed, and the least deviation from a ridiculous rule of propriety… would endanger their precarious existence”.

Evidence of life on Henrietta Street

The condition of the street in 1807, after the Act of Union:

“Henrietta Street, once the proud residence of the O’Neills, the Shannons, the Ponsonbys, the Kingsboroughs, the Mountjoys and the primates and chiefs of our religious establishments, is now a heavy melancholy group of monuments of our recent prosperity, it is literally covered with grass.” The Irish Magazine

Two descriptions of 14 Henrietta Street from the 1850s, when it was the Encumbered Estates Court:

“A large old-fashioned mansion in Henrietta Street, Dublin, was taken for the commissioners, the stable at its rear being enlarged into a court house, where the commissioners sat together two days weekly, and where the public sales of estates took place [...] the quantity of work which flowed in upon the court, especially in the years 1851-4 was in excess of all anticipations […] Little account was made of the usual office hours, or even of customary periods of vacation. The only anxiety was to clear off the heavy work in the offices as rapidly and efficiently as possible.”

‘The History and Statistics of the Irish Incumbered Estates Court’ in The Journal of the Statistical Society of London vol.44 No.2 (June 1881) pp.203-234

The court was held in “one of the houses in Henrietta Street- a small and quiet, but handsome street in the extreme north of the city of Dublin”. The courtroom in the coach house at the back of number 14 was a “large, chilly-looking room, without a ceiling between the roof and the floor, furnished with some rows of seats for the public, a small table covered with green cloth for the bar and the attorneys, and an elevated bench unadorned even with the royal arms, for the commissioners”.

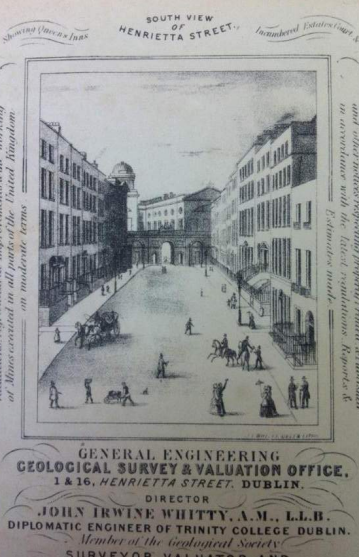

1860: An advertisement for General Engineering, Geological Survey and Valuation Office

ShopBook Now

ShopBook Now