Seán McLoughlin: The North King Street Bolshevik

StoriesPublished 20 April 2021

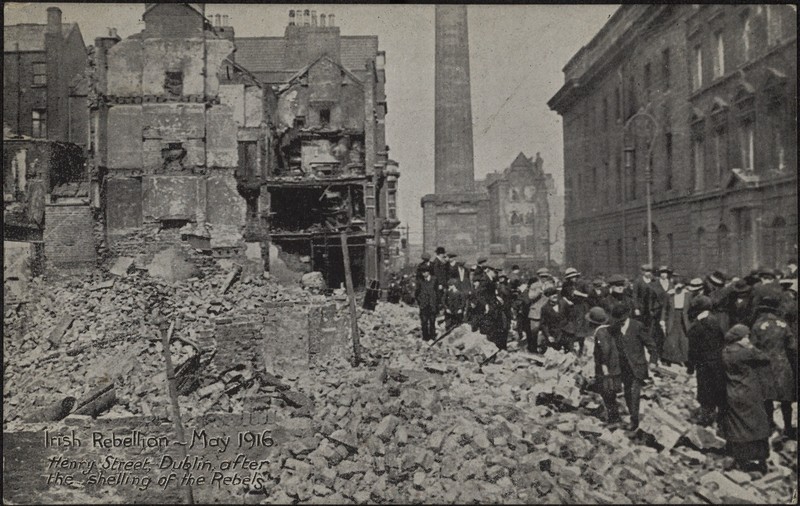

Postcard photograph, Irish Rebellion, May 1916 series. Henry Street, Dublin, after the shelling of the Rebels. Printed by The Daily Sketch for Easons, Dublin. Courtesy of the UCD Digital Library.

14 Henrietta Street is delighted to welcome historian, broadcaster, and curator, Donal Fallon, to write a series of blog posts about the building and its rich and varied history.

Below, Donal explores the legacy of the Irish revolutionary, Seán McLoughlin, who was born in North King Street.

Revolutionary roads

The streets around Henrietta Street contain some surprising connections to the revolutionary period and the on-going decade of centenaries.

Some of the stories connecting this area of the city to the Irish revolution are unmarked - Mahon’s Printers on nearby Yarnhall Street produced the IRA’s newspaper, An tÓglach, during the War of Independence and was fundamentally important in the propaganda war. Other stories are honoured in the landscape - at Mount Carmel, a building is named Áras Skinnider, in honour of the Irish Citizen Army veteran Margaret Skinnider. Nearby, a plaque marks the location where Kevin Barry - who had earlier participated in a raid for arms on Henrietta Street itself - was captured at Monk’s Bakery in 1920.

One plaque, beside North King Street’s Centra, eluded most of us until recently. Dedicated to ‘the forgotten Boy Commandant’, it commemorates Seán McLoughlin. Forgotten is certainly a fitting word - historian Charlie McGuire christened his biography of McLoughlin Ireland’s Forgotten Revolutionary.

A young rebel

Born on 2 June 1895, Seán McLoughlin spent the first twenty years of his life living at North King Street. His father, Patrick McLoughlin, was a founding member of Jim Larkin’s Irish Transport and General Workers’ Union (ITGWU), while his mother, Christina, was recalled as an ‘extreme nationalist’ by those who knew her. They had six children. McLoughlin’s older brother, Danny, enlisted in the British Army war effort and was blinded as a result of the use of mustard gas at the Battle of Passchendaele. Seán’s battles would be at home - he joined the republican boy scouts of Constance Markievicz, Na Fianna Éireann, in 1913. McGuire’s biography notes that in that same year, the Lockout had a transformative effect on Seán, as ‘this attempt by the Dublin employers to break the young transport union and all that it stood for, turned into a six-month long class war, the most bitterly fought dispute in Irish labour history.’

Despite its name, the ITGWU was not primarily a union of transport workers, but general labourers. The unskilled working class, those who lived in streets like North King Street and Henrietta Street, formed its backbone. In a city of so much underemployment, unionising such workers was a new departure. Patrick McLoughlin organised workers on the railways and in the Dublin dockyards, something which greatly influenced his son.

Seán became a member of the Irish Volunteers, which may seem peculiar given the strong involvement of his family in the labour movement. This was not entirely unique however, as trade union officials like Peadar Macken and Richard O’Carroll were also enlisted in the Volunteers. In some cases, these men were also enlisted in the Irish Republican Brotherhood - the Fenian movement - which maintained a close relationship to the Volunteers, and no influence over the Citizen Army.

Bravery and a stroke of luck

McLoughlin participated in the Easter Rising and perhaps its most daring chapter - playing a leading role in the evacuation of the GPO garrison, through the chaotic laneways surrounding Moore Street. The intention was to bring the Rising to the heart of this area, and the Williams and Woods factory, a large concrete building they felt could offer some resistance. In the GPO, Seán MacDiarmada outlined his fears to McLoughlin, that ‘we are not going to be caught like rats and killed without a chance to fight.’

As a result of his brave role in the evacuation, James Connolly bestowed upon him his own uniform markings, promoting McLoughlin on the spot - the origin of the name ‘Boy Commandant’ which he would carry onwards. At Richmond Barracks, a British officer on seeing McLoughlin's youth removed the insignia. As historian John Gibney has noted, 'in doing so, he reduced McLoughlin to the anonymity of the rank and file and very likely saved his life.'

McLoughlin’s lucky escape at Easter Week was matched by his good fortunes in the Spanish Flu pandemic, believed to be in a dying condition, McGuire notes ‘he was taken to North Brunswick Street hospital, where he remained until after the close of war.’

Socialism and Ireland

The world was changing in significant ways. McLoughlin and some other young 1916 veterans, including Paddy Stephenson and Roddy Conolly, found themselves increasingly drawn towards the Soviet revolution. McLoughlin and those around him were formative in the new Socialist Party of Ireland, and enlisted in the reformed Irish Citizen Army. His work in the years of the war in Scotland did much to build bridges between Irish revolutionaries and the confident labour movement on the Clydeside, while McLoughlin and those around him placed tremendous faith in the guiding hands of the Bolsheviks, writing to Moscow that ‘if once a worker’s republic was established in Ireland, the effect in Britain would be tremendous. It would practically mean that the same thing might occur in Britain.’

McLoughlin and those around him in the small communist circles of revolutionary Ireland found themselves increasingly marginalised. Following Civil War defeat, a war in which he and those around him took the republican side, McLoughlin worked alongside Jim Larkin in Dublin for a period in the 1920s, an active organiser in the Inchicore rail strikes, motivated by a long standing demand for improved pay and conditions. McLoughlin found Larkin difficult, insisting that ‘the day Larkin and his brutal and underhand tactics are banished from the arena of working class struggle, that day the workers will have made a huge leap towards emancipation.’ Larkin, a famously difficult figure to work alongside, could prove both a blessing and curse to the Dublin labour movement, as McLoughlin discovered.

Far from North King Street

McLoughlin lived his final years in exile, far from North King Street, McGuire’s research answering many questions on just what became of him. He applied for a Military Pension in 1947, though he did not receive one until five years later. There is much frustration evident in pension applications, but few match the tone of McLoughlin, furious to be ‘treated as if I were a beggarman by people who rose to power and position on the efforts of people like myself.’

McLoughlin died in England in 1960. North King Street’s connection to the Easter Rising in popular memory is primarily with the tragic events that occurred there in the closing stages of the Rising, when civilians were killed in and around their homes in what would become known as the ‘North King Street Massacre’.

McLoughlin is a reminder that the street produced revolutionaries too. His plaque is a reminder of what can sometimes hide in plain sight.

Donal Fallon

Donal Fallon is a historian, broadcaster and curator from Dublin. Formerly Historian in Residence to Dublin City Council, he is the author of numerous studies of twentieth century Dublin, including The Pillar: The Life and Afterlife of the Nelson Pillar (New Island, 2013). He produces the Three Castles Burning podcast and has contributed to publications including Jacobin, Dublin Historical Review, Saothar and The Irish Times. He is a graduate of Maynooth University, University College Dublin and the Ulster University, and lectures with the Lifelong Learning department of University College Dublin.

ShopBook Now

ShopBook Now